In 1957, artist James Houston, a resident of the Cape Dorset community for several years, became the Canadian civil administrator for the Inuit settlement of Cape Dorset on an island in Nunavut, Canada. Here, he encouraged Inuit people to use their traditional handicraft abilities to create saleable works of art.1 From this practice, the West Baffin Eskimo Co-operative was created. The co-operative sought to produce an infrastructure for the creation and sale of Inuit art to European and American art collectors. The organization encouraged artists to channel their carving and sewing abilities into drawing and printmaking and paid them for the work they created. Furthermore, the co-operative carefully organized distribution and sale of the resulting works, often through the creation of illustrated print catalogues specifically directed towards Western art markets.2 The establishment of an art market was especially crucial at this time, as many Inuit continued shifting from a migratory, self-sufficient economy to a settled and more trade-heavy economy. Up to this time, the Inuit people had been presented in anthropological and media sources as “timeless” and “untouched” by Western society.3 Accordingly, Western consumers expected that element to be reflected in the art of the Inuit. The Euro-American art market was especially interested in depictions of the traditional Inuit ways of life, and Houston encouraged the creation of art that fit into that narrative.

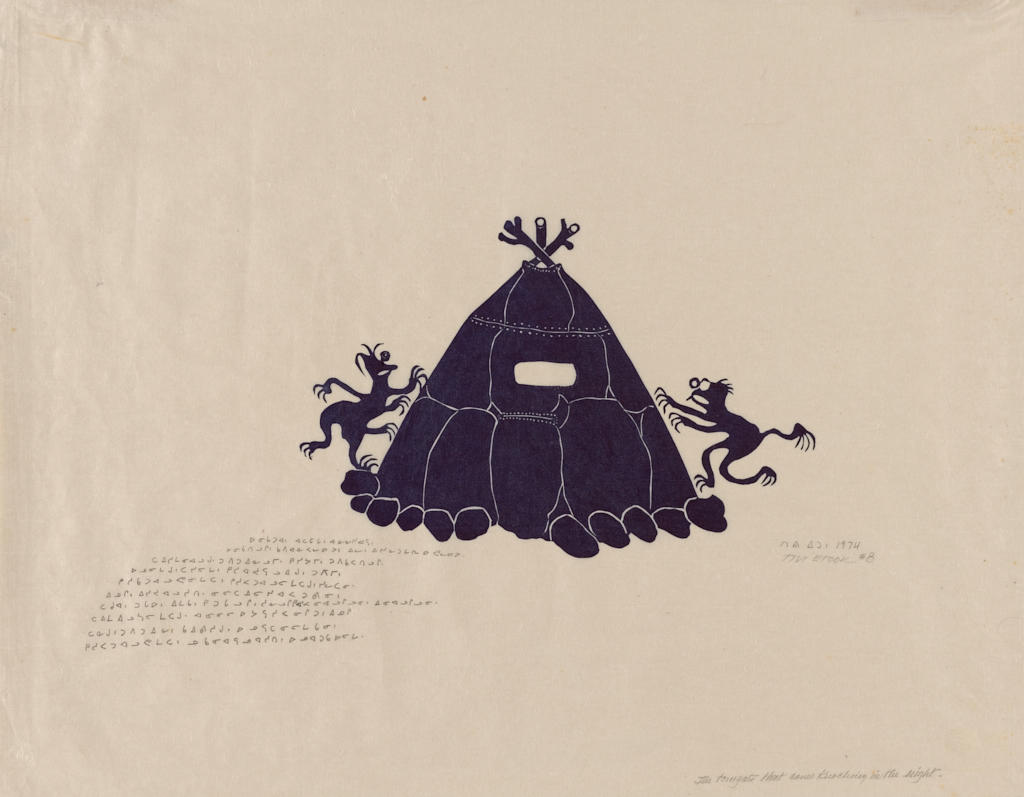

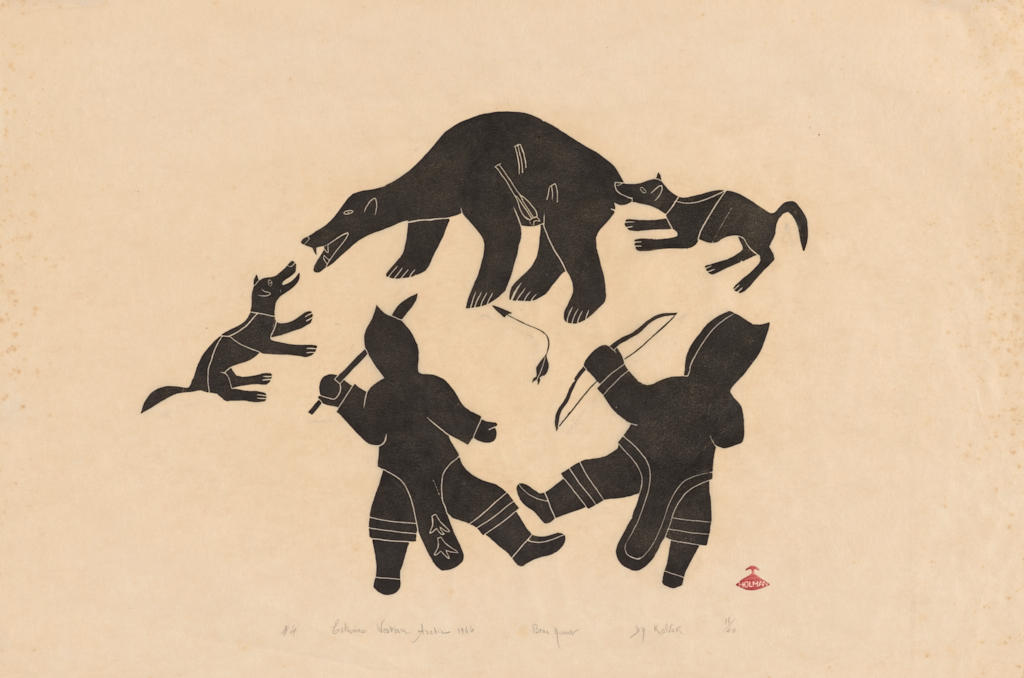

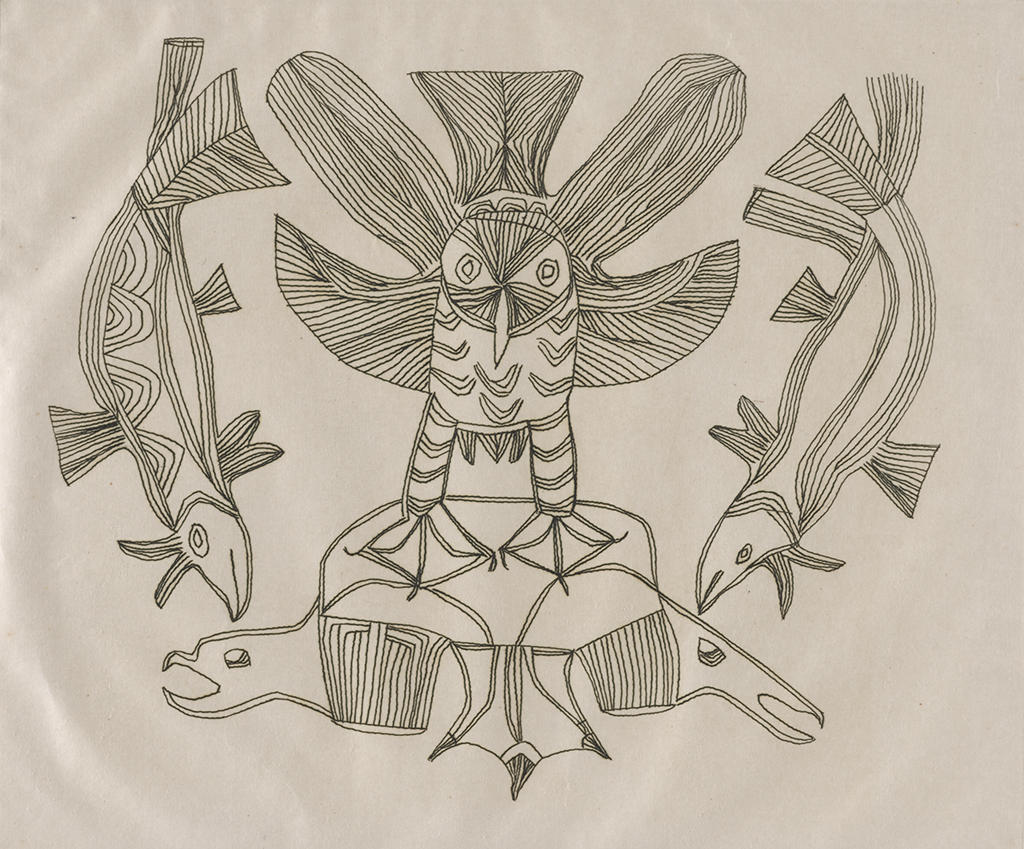

Specifically, Houston encouraged the Inuit to make art that involved monsters or traditional practices.4 The vast majority of the stone relief prints in the RISD Museum collection reflect these strategies. In the late 1970s, James Houston and his wife, Alma, donated to the RISD Museum a collection of approximately thirty prints and drawings that contain many explorations of traditional practices and mythical creatures. For example, Bear Hunt, pictured above, shows figures attacking a bear with a spear and a bow and arrow. Inuit hunters had used guns since their earliest interactions with British whalers in the 19th century, but Helen Kalvak chose to represent the old way of life, as opposed to more common practices of the time.

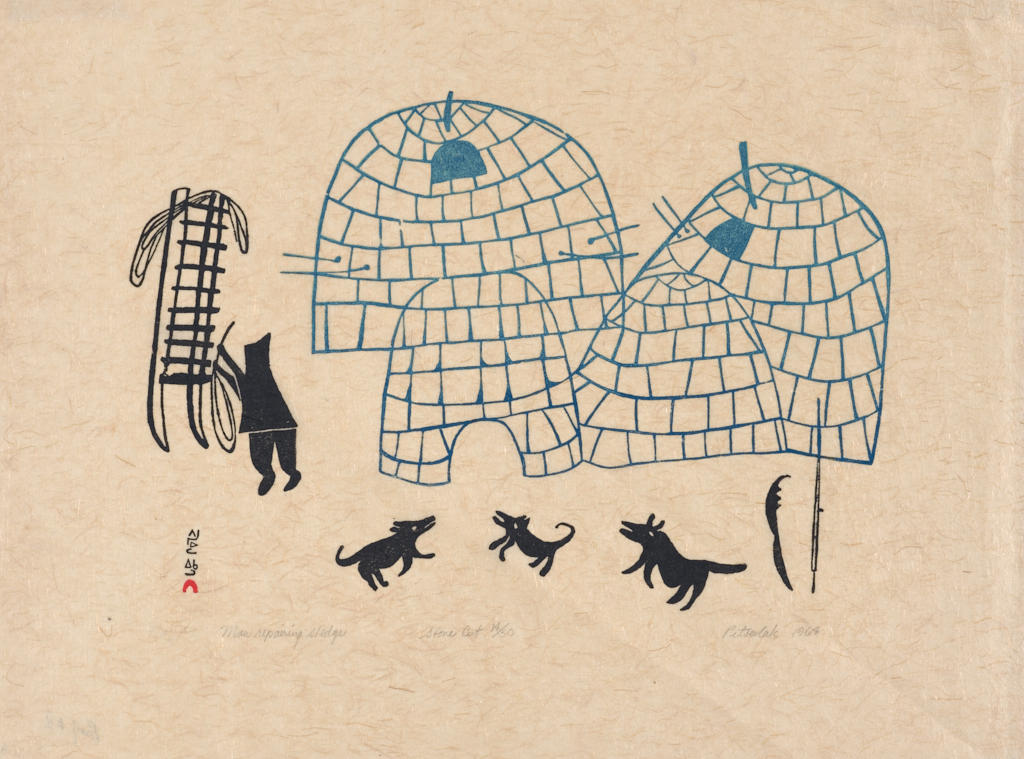

The efforts of Houston and the Inuit artists were not, however, met with universal acclaim. Instead, some art critics saw the project as pandering to the romanticism of the Western art market and ignoring the daily realities of modern Inuit life, which included television, supermarkets, and snowmobiles, not igloos and dog teams.5 Artists lived in clapboard homes and had access to television and supermarkets, but they chose to represent the life of their ancestors. Despite the fact that she lived in a modern town, Pitseolak (1907–1983), in Man Repairing a Sledge, presents a man at work on a sled while surrounded by igloos and traditional weapons. The RISD collection of Inuit prints is entirely lacking in references to modern life, and instead is made up of artists’ reminiscences on the “old life.” In reality, the “pure” Inuit life as presented in sources such as Nanook of the North (the 1922 film about life in the Arctic, later revealed to be largely staged) never really existed. Since 1000 CE, the Inuit regularly interacted with European travelers and traders, even traveling to European countries on whaling ships as far back as the 19th century.6 The desire for “purity” in Inuit art, and the opposing criticisms of traditional themes, reflects expectations of a Western art market and art historical field that are inconsistent with the complexities of Inuit culture.

Some Western art historians in the 1970s expressed discomfort and disdain for the prints that came out of the co-op project, because they saw the introduction of modern amenities to Inuit life as positive. Inuit art, they argued, should not have to meet Euro-American ideals of what Native art looks like. Reflecting on the transition of the Inuit from migratory to settled lives and criticizing the Western art market’s expectation of arts depicting traditional activities, art historian George Swinton wrote, “No doubt, these changes are destroying the Eskimo’s indigenous culture, but they are also improving the tragic conditions of his life and are preferable to the purist’s romantic illusions.”7 With this, Swinton ignores the agency of Inuit artists to create works based in either their modern reality or their history. It also disregards the lived experience of the Inuit themselves. Inuit artist Pitseolak spoke about the “tragic conditions” of her early life, saying, “The old life was a hard life, but it was good.”8 Pitseolak continuously revisits traditional themes and explores the old life. She describes this life: “I had a happy childhood. I was always healthy and never sick… . We lived the old Eskimo way.”9 To present this old life was not simply pandering to an art market, it was exploring lived personal experiences and deep cultural histories.

Western art critics of the 1970s also sought to condemn the economic force behind the art’s creation. Edmund Carpenter, an art historian specializing in Inuit art, bemoaned the loss of the “practical” value of Inuit art in that Inuit traditional art consisted of ornamenting tools and clothing.10 However, it is clear that Inuit printmaking, and especially the printmaking emerging from the West Baffin Eskimo Co-operative, allowed Native artists to support themselves. This was especially valuable for female artists lacking another trade, a husband to support them, or both. Certainly economic safety is valuable, so the art is only no longer functional in the traditional sense of art that serves as a literal tool.

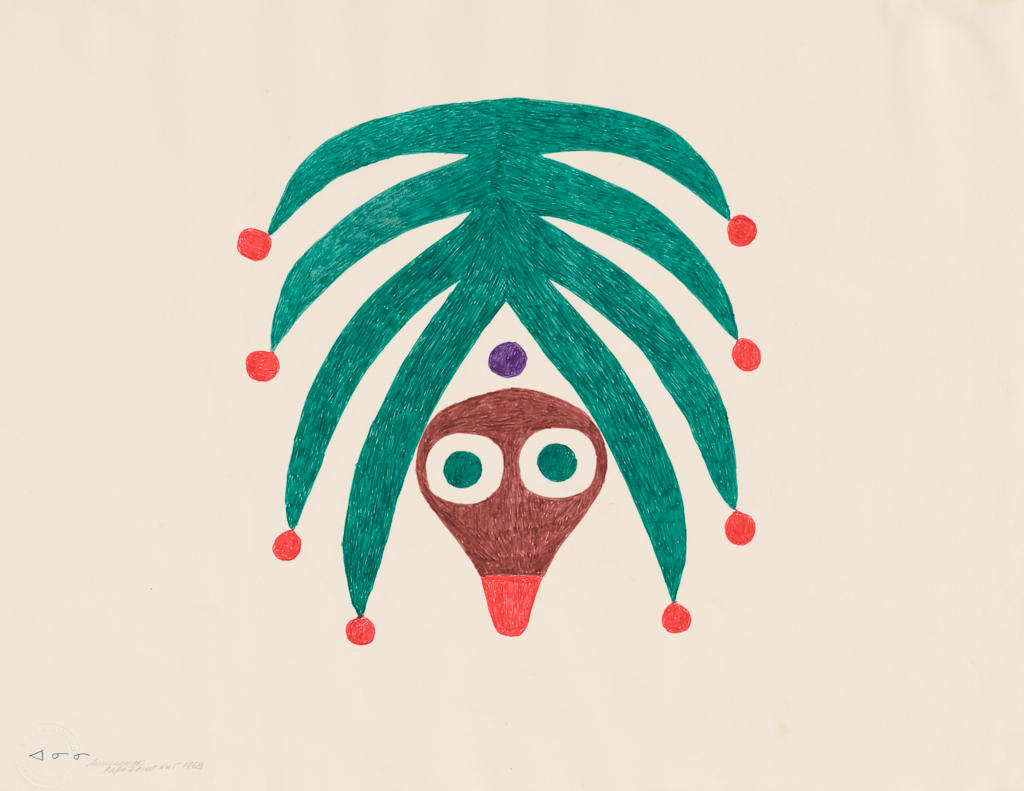

When I first opened the RISD Museum’s boxes of Inuit prints, it was this concept of art created for economic intent that first struck me. Looking at Anirnik’s Green Insect, I was amazed by the simplicity and charm of the creature’s small face peering out from beneath aestheticized leaves. I felt scandalized that this fascinating work of art was created “just” to be sold. I now see that my expectations were much like Edmund Carpenter’s: a Western expectation of Inuit purity. I realized that I would never stand before a Raphael and wonder how much he was paid or how true the art was to his lived experience. In expecting “purity” or “honesty” of Inuit art, we are not regarding Inuit prints as art. We should not demand of them that they fit into our idea of the Modernist progression of art towards abstraction or sit outside of the canon as perfect examples of a whole culture. As Inuit artist Pitaloosie Saila said, “You don’t just do drawings … you express yourself. It is also a way of life, a part of life. Life is sometimes heavy … you have to be able to express yourself, sometimes it comes out through art … I am just doing what I know how to do best.”11

Hannah Gadbois is the International Fine Print Dealers Association intern for Summer 2016 at the RISD Museum and a recent art-history graduate of UMass Dartmouth

- 1Jean M. Humez, “Pictures in the Life of Eskimo Artist Pitseolak,” Woman’s Art Journal 2 (1981): 31, accessed July 7, 2016. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1357979

- 2Courtney R. Thompson, “Inuit Prints, Japanese Inspiration: Early Printmaking in the Canadian Arctic,” Art in Print 2 (2012): 32–33, accessed May 21, 2016. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43045418

- 3Ann McElroy, Nunavut Generations: Change and Continuity in Canadian Inuit Communities (Long Grove, IL: Waveland Press, 2008), 25–30.

- 4Humez, “Pictures in the Life,” 32–33.

- 5Janet Catherine Berlo, “Portraits of Dispossession in Plains Indian and Inuit Graphic Arts,” Art Journal 49 (1990): 136, accessed July 7, 2016. http://www.jstor.org/stable/777193

- 6McElroy, Nunavut Generations, 25–33.

- 7Gerald McMaster, introduction to Inuit Modern: Masterworks from the Samuel and Esther Sarick Collection (Vancouver: D&M Publishers, 2010), 25.

- 8Dorothy Eber, Pitseolak: Pictures Out of My Life (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1991), 50.

- 9Ibid, 33.

- 10McMaster, Inuit Modern, 26.

- 11Odette Leroux, Marion E. Jackson, and Minnie Aodla Freeman, eds., Inuit Women Artists: Voices from Cape Dorset (Vancouver: D&M Publishers, 1994), 10.